Saturday, December 31, 2011

New Year’s Day in Paris in 1858

Excerpts from: ASPECTS OF PARIS. BY EDWARD COPPING. LONDON: LONGMAN, BROWN, GREEN, LONGMANS, & ROBERTS. 1858.

CHAP. II.

PARIS ON NEW YEAR'S DAY.

IF you would see Paris under its gayest aspect, you must see it on the Jour de l'An, or New Year's Day. The Jour de l'An is the most popular of all French holidays; it is the Christmas Day of France. Paris is lively enough on other festivals, but on this she becomes thoroughly gay. Work almost entirely ceases. The ouvrier puts aside his implements; the ouvrière lays down her needle; the clerk flings away his pen; the merchant closes his ledger; the journalist shuts up his bureau; the judge doffs his gown. The unhappy shopman alone has no respite from labour. Rarely, indeed, does he work so hard as on the Jour de l’An. No wonder! All Paris goes out shopping to-day, and he has all Paris to serve.

By noon the great movement has fairly begun. Promenading purchasers fill every street; the arcades overflow; the Boulevards are entirely submerged. From the Madeleine to the Château d'Eau, and from the Château d'Eau to the Madeleine, four goodly miles, I trow, the pavements on both sides are occupied by a slowly moving mass of human forms. It is impossible, be assured, to move quickly. Your pace must necessarily be that of the tortoise. Never mind! The hare is fast asleep to-day. You need not fear that he will outstrip you.

If the pavement were not doubly encumbered, you would find it impossible to accelerate your speed. Though you should have no more taste than a Hottentot, no more poetry than a paviour, you must stop to gaze at the glittering objects displayed in every shop window. And yet to loiter here is perilous. Your gold pieces are in danger. If you would return with an unlightened purse and an untroubled conscience, retire at once. There is a conspiracy to-day among the Paris shopkeepers to rifle and strip you. Refuse to listen to the voice of prudence, and they will leave you as coinless as was poor Jean-Jacques when he arrived in Turin under the conduct of the worthy Sabrans.

If, however, you are determined after this warning to brave the dangers of the Boulevards, your expenditure be upon your own balance sheet! Follow me.

Did you ever before see such a display of charming objects, so calculated to decoy artless woman and seduce unsuspecting man? Every tradesman seems to have opened a fancy fair. See! the linen draper puts forth his most ethereal gauzes, his most glossy satins, his most tender velvets. The tobacconist displays the most gorgeous hookahs, the most magnificent meerschaums, the most fanciful pouches, the richest and rarest snuff-boxes. The bookseller is all a-blaze with brilliant bindings. Nothing but resplendent gift books, gilt edged, gilt lettered, and gilt covered, are to be seen on his counters. Even Corneille and Racine would be excluded from this company of well-dressed tomes if they made their appearance in paper dishabille. Then the china-merchant arranges in the most enticing order his choicest porcelain vases, his most glittering cut glass, his most alluring cups and seductive saucers. A man might contentedly leave off tea-drinking forever, if he could but for once sip his souchong out of this ravishing crockery. And then the stationer, where has he obtained all those ink-stands, which of themselves might tempt any man to rush into print; and those piles of fancy note paper, as delicately tinted as a maiden's cheek; and those writing-cases, which seem almost too delicate for even the hand of Beauty to rest upon? Where, indeed! The toy-man might tell us, perhaps, for evidently he has credit at the same establishment. Yet, no! His merry-eyed, rosy- cheeked dolls, were never made by mortal hands. They must have been born of other dolls, some good old lady from fairyland assisting them into life.

It is all clear enough now. Every Paris tradesman has fallen madly in love to-day in love with extravagant display. Why even the apothecary adorns his windows with the most attractive patent medicines and the most pleasing surgical instruments. If there were an undertaker here about, depend upon it he would share the general infatuation. He would treat us to rows and rows of charming little baby- coffins of polished oak, intermingled with the choicest specimens of leaden ware for adults.

But the most brilliant displays we have yet to see. Yes! hitherto we have been merely dazzled; now we are to be fairly blinded. A man may look at linen drapers, stationers, china merchants, book-sellers, tobacconists, and pass on unscathed, perhaps; but not thus will he pass the shop where knick knack nothings are sold or that where sweetmeats make mute appeals to the greedy stomach of youth.

Knick knack nothings! Imagine the indignation of a polished Paris tradesman upon hearing his objets d’art thus contemptuously designated. I retract the expression. We should have a better name for all these beautiful trifles in which art strives to unite itself to utility these taper stands, toilette boxes, jewel boxes, wafer boxes, scent bottles, clock cases, pin receptacles, &c.

Granted, that art is sometimes here put to mean employ, as Minerva would be if she were to go out charring. Yet see how it refines and softens everything it touches! Look at that stand for taper and lucifer matches in the centre a little boy and girl are reading a book; they evidently read by the light of the taper; should it go out are not the matches all ready on the other side to rekindle it?

Fortunate age! In our forefathers' days art remained shut up in the picture gallery or the sculpture museum a proud beauty who scorned the vulgar gaze. Now she condescendingly puts on a homely mien and comes forth into our humblest dwellings, bringing brightness into their most obscure corners. But at last we have arrived at the most splendid stall in the fair. We are at the sweetmeat shop of which I spoke.

This a sweetmeat shop! Why it's the last scene of a pantomime without the coloured fires! a Bower of Beauty, Hall of Radiant Light or Palace of Dazzling Splendour. Where is the good spirit who ought to be somewhere near about waiting to come in on her magic car? The good spirit, my gentle and simple sir, is behind the counter, quite ready to serve you, if you wish to buy anything, but in no mood to listen to your theatrical rhapsodies.

Buy! who talks of buying here? This is an art exhibition not a lollypop shop. Those bonbons are too exquisite to be eaten. I should as soon think of eating the Venus de Milo or the Diane Chasseresse. Eyes, not stomachs, surely, are to be feasted with these beautiful coings, these charming abricots, these graceful cerises; these delicate mandarines, mirabelles, Reines Claudes, brochettes, marrons glacés, angéliques, pastèques, and calissons d'Aix!

Why! look at the boxes and baskets in which they are contained. They would grace the boudoir of a fairy. A fairy! If Titania were to come here shopping, Oberon would be forced to disclaim all responsibility for her debts in order to save himself from the Bankruptcy Court or Clichy. Come away, man, come away, while yet another six-pence is left in your pocket.

Shops, more shops! Yes, the very pavements axe covered with them. All along the main Boulevards and in many of the chief thoroughfares you will see line after line of temporary shops stretching away. They are mere stalls unsightly edifices of rough deal, hastily knocked together, but they add amazingly to the bustle of the streets. Their proprietors are mostly small tradesmen or hucksters, who are allowed by the municipal authorities, in accordance with time-honoured custom, to establish themselves in this manner upon the public pavement for about a week before, and a week after, the Jour de l’An. Purchasers whose purses will not enable them to visit in safety the shops we have just been looking at come, without fear, to these temporary establishments, for the objects they sell are of inferior quality and of low price. In these stalls there is a strange succession of the useful and the ornamental. In one you will see, perhaps, devotional images; in the next, fleecy hosiery. Side by side with illustrated gift books, you will find cheap fire-irons; immediately after porcelain vases come brushes and brooms.

You may buy almost anything, indeed, in these wooden marts. The dealers are prepared to supply every want. Toys, trinkets, sham jewellery, drapery goods, stationery, fruit, bonbons, pictures, cakes, pocket-handkerchiefs, crockery, cutlery, bronzes, cravats, thermometers, purses, walking-sticks, stereoscopes, papier-maché tea-trays, hat-pegs, book-cases, chairs, hair-brushes, telescopes, pots and pans, almanacs, pipes, basket-work, artificial flowers, plaster casts, furs, stags' horns, measurement rules, Berlin wool patterns; all may be had in these street storehouses. How much per cent, under prime cost none but an advertiser would be bold enough to state.

But why all this unusual display, you ask, after passing miles of stall and shop, miles of shop and stall? To answer is not difficult. The Jour de l’An is a day on which everybody in France makes presents. As poor as a pauper, or as stingy as charity must be the man who does not open his purse strings on this joyous first of January. Be his circle of acquaintance ever so small, he cannot pass round it without the aid of his generosity.

Presents are made to everybody to-day. Presents to mothers, to fathers, to sisters, to brothers, to wives, to daughters, to sons, to cousins, to uncles, to aunts, to nieces, to sweethearts, to mere friends and acquaintances. Ladies and children come in, of course, for the lion's share. If you are on intimate terms with a family, not only the younger members of that family, but their mammas also, expect new year's gifts, or étrennes as they are called. The cost you will be put to, for these presents, is no trifle. A young man of but moderate means, and with but a moderate number of friends, rarely spends less than a hundred francs four pounds sterling upon his étrennes. People whose means are more ample, will disburse ten times that sum. The amount spent every year in Paris on the Jour de l’An for toys alone, is estimated at one hundred and eighty thousand pounds sterling!

The étrennes of the superior shops are, as a rule, of the most expensive kind. A box of sweetmeats seems a very simple affair, and so it is when the box is mere deal, and the sweetmeats homely caraway comfits. But this simplicity would not suit Parisian taste. The bonbons of the Jour de l'An are of the most luscious kind; the boxes, elaborately worked and adorned, are of papier-maché, mother of pearl, or carved wood. I have seen them as high as twelve hundred francs -- forty-eight pounds sterling and there are some even dearer. Very pretty presents these, as it seems to me, for New Year's Day.

People generally give away these étrennes, or humbler ones of a similar kind, with a cheerful spirit and a smiling face. This is only natural. Friends whom we esteem, and relatives whom we love, have the key of our hearts; and that key, as is well known, unlocks our money-chest. But there are other people who in no way enter into our sympathies, to whom we are as it were compelled to give, and to them we extend our generosity with miserly reluctance.

I have said that the Jour de l'An is the Christmas Day of France. It is the day after as well. A host of persons, who have no more right to ask alms of you than they have to stop you on the highway, assail you now with demands for unearnt money. The weak-voiced, feeble-smiling Auvergnat, who brings you water every morning in pails, after the manner of the middle ages, (such extraordinary inventions as Water Companies and New Rivers not yet having penetrated into the most civilised capital in the world,) is perhaps at the head of this black band. Then comes the charbonnier, who supplies you with wood and coal; the man who brings you your paper in the morning; the servant whom you regularly pay every month for serving you; the blanchisseuse who washes your linen; the concierge who peeps into your letters, and otherwise renders you important aid; the butcher boy who brings you meat; the baker boy who brings you bread; the grocer's boy who brings you grocery. Your entire morning is spent in responding to the pitiful demands of these people. If only sixty or seventy francs also are spent, you may think yourself lucky.

In no place are you safe from the banditti of the Jour de l’An. Exhausted, perhaps, by the voluntary acts of generosity which have been wrung from you during the morning, you take refuge in your restaurant, and order a déjeúner. The garҫon smiles upon you as you enter, he smiles upon you as you sit down, he smiles upon you when you have finished your meal.

Nay, so amiable has he become, that he brings you, unasked, an orange, which he, still smiling, trusts you will accept. That orange costs you a five franc piece. Your digestion being thus disarranged, you make the best of your way to the café, and take a petit verre, or a little black coffee, exactly of course as you would take a blue pill or a dose of quinine. But here too you meet with a smiling garҫon, who obligingly offers you a cigar tied up with a piece of red ribbon. Your hand is again in your pocket. For cigars cost as much as oranges to-day. As a last resource you fly to your reading-room, hoping to wrap yourself up in a journal, and thus remain concealed. But the surly attendant, who for a whole year has made you wait until six o'clock for the evening papers, and who has always told you that the "Débats" is engaged three deep, at once spies you out, and with a smile even upon his face wishes you all sorts of compliments upon this most auspicious day.

You get rid of him with a heavy groan and a gratuity by no means light, and wander forth into the streets, striving to forget your indignation by mingling with the happy groups you see there. You are really forced to give in every direction to-day. If you are not on sufficiently intimate terms with a friend to make him a more expensive present, you send him your card. You leave it at his residence with your own hands, supposing your politeness be strong enough to support you through this act of pedestrianism, and turn down one of its ends to indicate that you have been your own messenger. But if your legs refuse their office, the postman's will be more obliging. To those you can make appeal. There is, in fact, a special postal regulation respecting cards sent through the post-office on the Jour de l’An. If they are enclosed in an open envelope they will be delivered in Paris for five centimes instead of ten, the usual price of a single letter. The number sent in this manner is consequently enormous. The unhappy postman, as may be believed, has no holiday on New Year's Day. Almost from early dawn he is abroad heavily laden with his pack, his pack of cards. How gladly would he let some one else deal them for him this day!

We will take one more look at the city ere the day wanes and the early night comes on.

It will not be a gloomy night, rest certain; café, cabaret, and restaurant will be filled with a merry company; the shops, even after midnight chimes have sounded, will still be brilliant and bustling as the last labours of the day draw to a close; the pavement will still echo with the tread of many footsteps.

And now, while yet an hour or two of lingering light remains, how look the streets?

They are still filled with the same crowd that occupied them at noon; the same, except that it is a trifle less numerous. It is even gayer, however, than before. All care, in fact, seems to have fled from Paris to-day. There are no more pouting children; no more frowning wives; no more grumbling husbands; no more melancholy bachelors. Cheerfulness and content sit on every face.

Look! the halt, the lame, the blind, and the simply indigent have been allowed to come forth into the streets without let or hinderance, without police interference or restriction, to draw upon the stores of kindly feeling which everywhere abound in Paris to-day. Ordinarily only a certain number of these poor sufferers, duly registered and ticketed, are allowed to appeal for charity on the public way, for even beggary in Paris is a monopoly. To-day, however, the trade is free.

Indoors, as well as out of doors, there are gaiety and happiness in Paris. There is a public reception at the Tuileries, and all sorts of étrennes in the shape of honours and promotions will be given to numerous functionaries. There is a private reception in every household. Friends and relatives visit each other who, perhaps, have been separated by distance or social position all the previous year. They would not miss the warm embrace, and the loving words, of the Jour de l’An, for all the good or evil fortunes that might happen during the next twelve months. There will be many a gay party to-night, when the visits of the morning are over and the last present has been made. Many an old dame will forget her years as she looks upon the happy group of sons and grandsons clustering round her. Back to the days so distant, but which seem so near, will she turn once again; back to the days when, light of foot as of heart, she danced 'mid a merry circle, gayest of the gay. Ah! when others dance now, she sits all alone in her chair. But how time changes us!

If old age is happy, how much more happy is youth! Look at that glad band of little ones! How proudly they display the beautiful gifts they have received! How they pet and hug the new doll or the new gun which has been given to them! Neither doll nor gun will be safe to-night except beneath their pillows, depend upon it. How lovingly they prattle and play! What fine games they have at colin-maillard, main-chaude, and pigeon vole! And even when sleep has fallen heavily upon their eyes they will still be happy. While yet the fond mother held them so securely in her arms, as they sank into slumber, they had wandered far away far away to scenes where even her watchful love cannot follow them. What would you or I give, oh reader, to have such dreams as they will have to-night?

But midnight has sounded. The happy day is over. We must wait another year for another Jour de l’An.

Another year! What a sad and a gloomy time we shall pass, perhaps, ere we have crossed the limits of this upon which we have just entered.

Courage, courage, faint heart! A day like this will shed its radiance far in advance, and light us over the uncertain road we have to traverse.

New Year’s in Antarctica 1911-1912.

Extracts from: The Journal of Captain Robert Falcon Scott, Royal Navy, as he attempted to reach the South Pole in 1910-1912.

Note: During this venture, Scott led a party of five which reached the South Pole on 17 January 1912, only to find that they had been preceded by Roald Amundsen's Norwegian expedition. On their return journey, Scott and his four comrades all perished from a combination of exhaustion, starvation and extreme cold.

31 December, 1911 New Year's Eve

Camp 53

The second party deposited its ski and some other weights equivalent to 100 lbs. I sent them off first; they marched, but not fast. We have been rising all day.

We had a good full brew of tea and then set to work stripping the sledges. That didn't take long, but the process of building up the 10-feet sledges now in operation in the other tent is a long job. Evans PO and Crean are tackling it, and it is a very remarkable piece of work. Certainly PO Evans is the most invaluable asset to our party. To build a sledge under these conditions is a fact for special record.

We will put a depot here and call it the 3 Degree Depot, since we are so close to the 87th parallel.

There is extraordinarily little mirage up here and the refraction is very small. Except for the four seamen we are all sitting in a double tent—the first time we have put up the inner lining to the tent; it seems to make us much snugger.

10pm.

The job of rebuilding is taking longer than I expected but now it is almost done. The 10-feet sledges look very handy. We had an extra drink of tea and are now turned into our bags in the double tent (five of us) as warm as toast, and just enough light to write or work with.

Evans couldn't say what took them so long, and was acting very gingerly with his hand. Very curious.

1st January, 1912 New Year's Day

Camp 54

Roused hands at 7:30 and got away at 9:30. Evan's party going ahead on foot. We followed on ski. We stupidly had not seen to our ski shoes beforehand, and it took a good half-hour to get them right. Wilson especially had trouble. When we did get away, to our surprise the sledge pulled very easily, and we made fine progress, rapidly gaining on the foot-haulers.

We have scarcely exerted ourselves all day. We are very comfortable in our double tent. Stick of chocolate to celebrate the new year. The supporting party not in very high spirits, they have not managed matters well for themselves. Prospects seem to get brighter -- only 170 miles to go and plenty of food left.

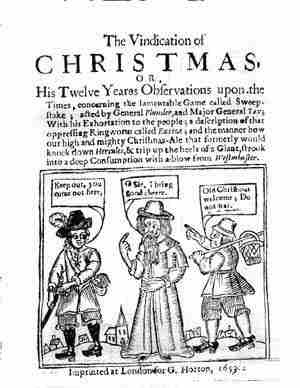

Wednesday, December 21, 2011

Justifying Christmas Celebrations in 1648

Extracted from: The Vindication of the Solemnity of the Nativity of Christ

Showing the grounds upon which the Observation of that and other Festivals is justified in the Church.

With a short Answer to certaine Quaeries propounded by one Joseph Heming, in opposiiton to the aforesayd practice of the Church. By Thomas Warmstry, D.D. Printed in the Yeare 1648.

Let us follow after things that make for peace, and things wherewith we may edifie one another. Rom. 14.19

Unto you is born this day a Saviour, which is Christ the Lord. Luk. 1.11.

-------

Transcribers Note: This tract was published in 1648, during the English Civil Wars. The text was transcribed from a print of a microfiche. The original was somewhat difficult to read in some places. Where I am not able to make a good guess of a word or phrase, I will insert “[?];” this is especially the case when transcribing Latin. If any reader has access to a better copy, and may offer corrections, please email me. Grammar and spelling are unchanged.

-----------

The Vindication of the Solemnity of the Nativity of Christ, &c

Before I come to answer these Queries, that I may make way for the clearing of mens judgements, I shall briefly lay down the grounds upon which the observation of this, and other Festivalls is justified in the Church; which are these.

First, It is a thing not onely lawfull, but justly due unto God, that he should be praised publickly and solemnely for this, and other such like great blessings as he hath bestowed upon the Church by Christ, and that to this end the memory of them should be preserved in the Church.

Secondly, That for these ends, the Observation of a yearly day of memoriall is a meanes conducible in it selfe, and approved by God in Scripture, who made use thereof among the ancient people to summon and stirre them up thereby to the praise of God for those great blessings and deliverances which were bestowed upon them.

Thirdly, That the appoyntment of such dayes being conducible to those ends before named, which are Scripture ends, hath so far its ground in the word of God.

Fourthly, That the Church hath a power from God to promote those ends which are commanded in his word, by all kinds of meanes which are not contrary thereunto, and such a meanes is this appointment of days, which hath been with approbation practiced by the Church, even in the time of the Jewish Bondage, in the designation and ordaining of Festivalls yearely to be observed, which were not enjoyned by any expresse command of God, as is clearly to be seene in the institution of the Feast of Purim, Esther. 9. 17. &c. and of the Feast of Dedication, Machab. 4.59 honoured and confirmed by the presence of our Saviour, Job. 10.22.23.

Fifthly, That this power in the Church is, thoughly onobservedly, yet in cleare consequence, is confirmed by divers arguments from the allowance and practice of Adversaries themselves.

As first, looke what power private Ministers challenge, that they must much more allow the Church: But they challenge a power to appoynt times for publick worship, which are not expresly commanded by God as upon Lecture dayes: Ego, And there can be no reason why they should have more power to appoynt an houre or more in a day, then the Church a day or more in a yeare.

Secondly, There is as good reason that the Church should appoynt days of feasting, which are not commanded by God, as dayes of fasting, which are not commanded by God; since the end of the former is as exceptable to God, and more excellent then the latter, and hath no please against it, that lyes not equally against the latter.

Thirdly, That there is much more reason that the Church should appoynt solemne dayes for praising God for Christ, and for spirituall blessings, then for temporall ones: But the latter is allowed and practiced by the Parliament, as may appeare by the late Ordinance for the observation of the fifth of November, in memoriall of the deliverance of that very State, Church, and Religion from an outward descruction, which themselves now persecue; by the Army, in appoynting dyes of Thanksgiving for their bloody Victories over their brethren, in an impious way. Therefore the former, viz the appoyntment of solemn dayes for greater and spirituall blessings, cannot reasonably be condemned by them.

Sixtly, This appoyntment of dayes to the purposes aforesayd, is not one [?], as not lying in oposicion to any Law of God, but of excellent use and benefit to Gods people. 1. To preserve and refresh the memory of these great blessings. 2. To [?] up the people to the duties of praise. 3. To call upon the Ministers in their severall charges to study, and handle those great, and necessary parts of Christian knowledge. 4. To give so many opportunities for the assembling of the people to holy duties. 5. For the rendring of those great and mysticall blessings familiar unto the people, thereby that being fulfilled in this sense, that the Psalmist speaketh in the 9. Psal. One day telleth another, and one night certifieth another; there is neither speech nor language, yet their speeches are heard among them. Thusit comes to passe that the Calendar of the Church, & the Cycle of the Festivalls presents, in as it were an easie and familiar Catechisme unto the people, and doth instruct them almost whether they wil or no in the apprehensions of those high points and comfortable motions of the conception, nativity, Circumcision, Manifestation to the Gentiles, presentation in the Temple, of the death and passion, resurrection, Ascention of Christ into Heaven, and of the sending of the holy Ghost, to bring home the fruit of all; which are as so many parts of the holy Antheme of the Church, the Epiphonema, or clase of all which is in the Festival of the Trinity, which is unto all the rest as the Glory be to the Father, to the Sonne, and to the holy Ghost &c. at the close of a Psalme, calling upon us to give honour and praise unto the Trinity for all those incomprehensible blessings and benefits whereby the worke of mans redemption is perfected and brought home unto us: This wisedome and piety of the Church is not understood, nor considered by those heady and haire brain'd people, that waigh things in the corrupt scales of [?] their owne contradictory and antecclesiasticall spirit; but they that are sober and peaceable discover and admire it, and blesse God for it, and do foresee with sad hearts the designes of Satan moving against this Church of ours, by the abolishing of these and other usefull Ordinances and customes, to blot out by degrees the memory of the great and inestimable blessings of God in Christ, and to open the doore to prophanesse and infidelty: to the former benefits may be added, the mercy that doth hereby accrue unto servants, and the poore beasts in a relaxation of their labours upon such daies, the incitements that they administer unto workes of charity, neighbourhood, and hospitality; things very pleasing in the sight of God, howsoever disliked by those of this age that place religion in cruelty, Faction, and Sedition; and the nurcery, and supply that is thereby suggested unto the exercise of our spirituall joy, and delight in God, and his goodnesse.

Lastly, The authority of the Church both ancient and modern, both generall, and of this particular Church, coming upon us with all these warrants, and conveniences to serve the ends of God and Scripture, and strengthened by the power of the civil Magistrate, and by the authenticall Lawes of the Kingdome in those Acts of Parliament which have establisht these things, must either engage all that are within the verge of the Church, and of this Church and State especially, unto a peaceable and piroud obedience thereunto, or else leave the staine of Impiety, Faction, and of a turbulent and disorderly spirit, or else of folly and blindnesse upon all those that oppose it.

Indeed there is nothing free from temptations; but it is well said of one, as I remember, and may be well considered of others, that it is not (at least not alwaie) the infirmity, but the excellency of things that maketh them the matter of temptation: Abuses of things that are good must teach us wisedome and caution, but not set us upon confusion.

And truly there is need of more warines in the observation of these daies then hath been used by many.

1. That superstitió be avoided, that we thing not one day in it self better or more holy then another, but only so far as they are actually designed or applied unto the service of God: we must remember that these and other particular times, as places, are but circumstances in the time of the Gospell, the substance is in the worship and service that is given unto God thereupon, not in the observation of these or that particular day, which is in it selfe a matter of liberty, as the Apostle sheweth, Rom. 14.5 &c. Col. 2.16. And that may be a satisfactory reason why in the new Testament these things are not particularly, or expressly injoined in Scripture, because these are but matters of Order, and of liberty; not of absolute necessity, and therefore left to the moderation of the Church; but then we must remember that the liberty of Christians is first the right and interest of the Body, and then of the Members, who must not urge their particular interest against publique moderations and constitutions in these things; yes, it is a maine liberty that belongs unto the whole body of the Church, that she hath power to restraine the liberty of private Members by publique authority for the publique good; but Superstition must be avoided, as I have said; noe humane authority must impose these, or any such like things, as substantiall, unalterable, or absolutely necessary to salvation; but as matters of Order, as holy circumstances, and meanes conducible unto higher ends, and so and no otherwise they are to be received and obeyed by the people: according to this is that of the later learned Father of our Church, Non putandum plus sanctitatis uni disiinesse quam alteri, sed sciendum quod propter ordinem & praceptum Ecclesie alias[?] causas Jupra memoratas une die magis quam alio convenimus, ad hac exercitim sanctitatis.

And againe, Non putandum, &c. we are not to thinke that they Church of God is tyed by any necessity to the immutable observation of these particular festivall daies: Sed statuendum, saith be, dies bosce humana authoritate constitutes cademposse tolli & mutari, fintilitas [?] & necessitas Ecclesie id postulaveris, nam omnisresper quascung: Causas nascitur per casdem diss[?]lvitur; But it must be so judged, that these daies which are appointed by humane authority may be abolished, and altered by the same: where the profit and necessity of the Church doth require it; for all things are dissolved by the same causes whereby they are established: But then this ought to be done upon good and true grounds, and by a power equall at least to that that hath established them.

[Editor's Note: printed in the margin, near the top of this paragraph is the following text: “Bishop Davenaus upon the Coloss.c. 2.v.16.”]

2. There must be care taken that there be a prudent moderation used in the number of such daies, that nothing be imposed over burdensome upon the people.

3. That they be rightly imployed, not in Superstitious worshiping of Saints or Angels, as is in use in the Church of Rome, nor yet in riot, intemperance, or any other sinfull libety, as hath been the practise of too many amongst us, making little or not other use of such times, but to give themselves to idlenesse, loosenesse, and vanity; an evil that hath not onely violated the holinesse of these Festivals we speak of, but also the Lords day, which some have turned into Sabbathum Vituli aurie, into the Sabbath of the Golden Calfe, of which it is said, Exod. 32. That The people sate downe to eate and drinke, and rose up to play. Others into Sabbathum B[????] & Asinorum, the Sabbath of the Oxe and the Asse, spending it in calling and drinking, and doing nothing; and too many make little or no difference betweene that and other dayes: But onely in putting on their better cloathes, and giving themselves to none, or else worse imployment then all the rest of the weeke, as if bene vestiri & nibil agere, To be well attired, and to doe nothing were to celebrate the Christian Sabbath.

And indeed it cannot be denied, but as this hath been the ill lot that too many have cast upon the Lords day, and other Festivalls: So it hath been too too much the share of the Solemnities appoynted for the celebrating of the Birth of the Saviour, and the rest of the Festivalls that the Church hath joyned with in, which instead of being made dayes of prayse and thanksgiving to God, and of the exercise of other holy, christian, and charitable duties with that sobriety that becomes Christians, have been made dayes of riot, and gaming, and wantonnesse, and unlawful liberty, as if men were to sacrifice to the Devill for these great and incomprehensible mercies of God: A great and intollerable abuse of such blessed opportunities, and such as, (although it doth not at al justifie men in the abolition of them, but should rather have set them upon the Reformation of those miscarriages, and the restitution of such times unto the first and profitable institution of them, That these evils and corruptions being removed, the divine Solemnities, and Religious Duties might have been returned and advanced still amongst us, to the comfort of the Church, and the honour of the name of God) Yet they may justly provoke God to deprive us of the comfort of these joyfull Celebrities, which wee have so miserably abused to his dishonour, and the hurt of our selves, and of our brethren: But these being the errours of particular men, they do not blemish the constitution of the Church in these things, which intendeth not such times for such evill purposes, but for the service and honour of god, and the edification of his people. And therefore as it must be the care of all good Christians to seperate the abuses into practice. So it is their part and duty to yeeld a ready obedience unto so profitable and wholesome a constitution; and as in other Festivalls, so in this of the Nativity of Christ, &c. This being as it were the rising of the Sunne of righteousnesse upon us with healing in his wings, and that whereon all the succedent worke of our redemption and salvation doth depend: And therefore as this doth in an eminent and speciall manner chalenge our praises and solemne services and acknowledgments unto God for so great a mercy: So the Authority of the Church in appoynting a solemne time, for such solemne service doth serve an holy and Scripture end, very acceptable to God, and by such a meanes, which he himselfe hath approved, and allowed the Church of God to make use of, and doth justly require our obedience thereunto which wee cannot withdraw ordinarily, without making a breach in that Communion of Saints, which is both our comfort to enjoy, and our duty to maintaine.

And these grounds being thus layd, and well understood, I hope may satisfie any peaceable minded Christians, and arme them against all materiall temptations that your Queries (which you seeme to thinke such Giants) can offer against it; and therefore I might well enough perhaps set a period heere unto this present businesse: But lest you should thinke your selfe despised, or grow wise in your owne conceipt, and for your further correction, and the more full satisfaction of others, I offer you and them this short answer unto your Queries; and if you or any other shall thinke them in any thing wanting in that clearenesse which yours, and some other mens apprehensions may perhaps require; I shall by Gods grace be ready if I may be allowed liberty to doe it: To render all things out of question and to resolve all doubts that may rest behinde in a faire, calme, and Christian disputation, and discussion of the point with your or any other that shall in a sober and ingenuous way desire to enter into discourse with me thereabout.

In the meane time take this briefe Reply unto your Demands.

To your first Quære.

Whether such religious customs as are binding to all the Churches of Jesus Christ, out not to have sure footing upon the Word of God or Apostolicall practice?

Answer, That it is ground enough for the establishment of Customes in the Church, and to bind all Churches to the Christian observation thereof, so far as is required unto Church Customes, and matters of order. &c. That such Customs and Observations beingin themselves harmelesse, and conducible to those ends which Gods word preseribeth, are commanded unto us by the Authority of the Church Catholic; and because this Quære is somewhat too wide for the particular drift you aime at; give me leave to take away all doubt, to contract it a little by adding this Corolary: That in such things the Authority of any particular Church is sufficient to binde those that are within the Verge of it. The Examples of the Feast of Purim and of Dedication before mentioned will come in seasonably heere for the confirmation of this.

To your second Quære.

Whether you can substantially prove that Christe was borne on the 25 of December? And what your proofes are?

Answer. That because as wee have layd downe the designation of this or that particular is a thing in it selfe indifferent (though the day being knowne wherein such mercies were performed may seeme more convenient then another.) The maine thing that wee rest upon being this: That God may be solemnely praised for so great a mercy, and to this end, that that day what ever it be, which is set apart by the Church for that holy purpose be duely observed: Therefore although there is perhaps more to be sayd heerin then you are aware of; yet to make short worke, and that they may be the easilier satisfied, who are not able to examine Antiquities: I answer that it is not at all necessary for us to prove substantially that Christ was borne upon the 25 of December; it is sufficient for us that the Authority of the Church hath appoynted that day to performe the duty of praise therefore unto God, neither doe wee so much depend upon that day, but if upon good reson an equall Authority had designed any other, it might be indifferent to us: To that God may have his honour in the solemnization of his great mercies, whether in this moneth, or that moneth, on this day, or that day, is of small concernment, but in poynt of order, peace, uniformity, and obedience; to dote upon this or that day otherwise is superstitious.

To your third Quære.

Whether the celebration of that day (grant he was borne on it) can be clearely warranted by you from Scripture? And what your Scriptures are?

Answer, It is answered already in the Reply made to the two former, where you have been shewed, that it is neither necessary to be proved that Christ was borne upon that day, nor yet that there needes any particular Scripture warrant for the observation of such days, more then is expressed in the answer to the first, and the grounds that are layd before you, and so much hath been shewed wee have abundantly for this day. Viz. That the Church hath power to appoynt a day for so holy and excellent an end prescribed in Scripture, and warranted unto us by the practice of a Quire of Angells, of Simeon and Anna, Zachary and Eitzabeth, in the Divine Story.

To your fourth Quære.

Whether you can cleare it by sound consequence from the New Testament, though not set down there in toridem verbis?

Answer, That which hath been sayd may suffice, in that the celebration of this day is appoynted by sufficient Authority, for those ends which are commanded in the New Testament, as is the rendring praise to God for so great a blessing of the New Testament, and is a meanes allowed by God for such purpose, and conducible thereunto, as hath been shewed in the grounds.

To your fifth Quære.

Whether you can doe it by universall tradition?

Answer, That it is well knowne that the observation of this day hath been very Ancient, and doth appeare to be of universall reception; as (if leasure and opportunity would permit) might be manifested more abundantly, but for the present it may suffice to set down that notable testimony of St. Cyprian, a very Ancient Father, in his book de Nativitate Christs in initio. Adest (saith he, speaking of this Festivall of the Nativity of Christe) Christi inultum [?] de siderasa & diu[?] expectata Nativitas, adest Solemnit as inclita & in presentia salvatoris, grates, & laudes, Visitateri suo per orbem terrarum Sancta reddit Ecclesia. There is not present the much desired, and long expected Nativity of Christ; now is present that famous Solemnity or Festivall and the holy Church throughout all the World doth render thankes and praises to her visiter in the presence of our Saviour; and though it be sufficient to binde us; that so wholesome custome is enjoyned by Authenticall Authority in this Church and Nation, yet this and other testimonies that might be brought of the Antiquity and universality thereof, doe much strengthen the obligation that lies upon us, for the Religious observation thereof.

To your sixt Quære.

Whether (in case it can be evidenced by none of these, viz plaine Text, solled [?] Inference, universall Tradition) it be not a meere humane invention, and so Will worship? And how you will one day acquit yourselves before God, for placing, and crying up mens Inventions, instead of the institutions of Jesus Christ? And whether it were not faithfull dealing with poore simple people to tel them that you have neither of these to warrant it?

I answer, it is already avoyded, and needeth no further Reply but this, first, that you have been taught if you can learne that wee have inference enough to satisfie men that will be content with evidence, and wish you would attempt nothing in the church, but what you could pleade half so much for: Secondly, that the observation of these particular dayes is not enjoyned by the Church, or used by us, as any substantiall part of worship, but as a circumstance of worship, and so can be no will-worship, no more then your appoynting this or that particular houre for preaching, and prayer upon a Lecture day, or the appoynting of dayes of thaniksgiving for Victories, for temporall deliverances, or of Publique Fasts by humane Authority (which as to the designation of the particular times are unquestionably of humane invention) and therefore to be accounted will-worship;p unless you will have the will-worship to lye in this; that these dayes we speak off are appoynted by good and full Authority, and that Christ is remembred therein; and now I intreate you to consider how you will one day acquit your selfe before God, for slandering and crying downe the wholesome orders and constitutions of the Church, to bring in division, confusion, and prophanation; and whether it were not faithfull in dealing with those poore simple people, that you or others have seduced into seditious and facious courses, and murmuring against Government and Order, to tell them you understood not things your selves, nor have taught them in the wayes of peace and righteousnesse, as you shoulde have done.

To your seaventh Quære.

(Since dayes and times commanded by God himselfe to be observed uner the Law, were, and are unlawfull under the Gospel) Whether dayes and times commanded by men, and not by God, under the Gospell, are not lesse lawfull.

Ans. Those daies and times that were commanded by God himselfe to be observed under the Law, were appointed by him for that time, as types and figures of the things of Christ, as Saint Paul well instruct you. Coloss. 2.16.17, and in regard of that typicall use, and will the Legall necessity thereof are vanished at the coming of Christ, which is the body and substance of those shaddowes; and therefore though they be so far become unlawfull, it will by no meanes infer that therefore those daies and times which are commanded by men with sufficient warrant from God under the Gospell as conducible meanes unto Gospell-ends, and for the solemnizing of the glory of God for Gospell blessings, should be concluded unlawfull, since the aforesaid reason of the abolition of those things of the Law, is no way applicable unto the Festivals, or other wholsome constitutions in the time of the Gospell, which are neither injoyned as types, nor as things necessary to salvation, but as matters of order, and circumstantiall meanes for the promotion of those substantiall duties, not opposing, but asserting and magnifying the great blessings that God hath revealed, and imparted unto us in, and by, the Messias now come. But for your further instruction, I desire you to take notice, that in the Feasts of the Jewes, as there was something Ceremoniall, so there was Something Morrall: that they were of unalterable necessity restrained to such and such particular times, that they were to be celebrated with such and such particular Ceremonies, and were therein types and figures of the things of Christ, and the time of the Gospell and that by the indispencible obligation of the divine præcept; in these and such like considerations, they were Ceremoniall and temporary, belonging unto that Sate of the Jewish Church; But if they be considered as they were certaine solemn and convenient times set apart for the publique worship of God, and for the more solemne testification of their thankfullnesse unto him, for those great blessings and deliverances that they received from him; This was, as a learned Authour tell us, morale, & natureale, & cumcateris omnibus gentibus commane, it was morall and naturall, and common with them unto other nations. Now though that which is typicall and ceremoniall be abolished as a shadow by the coming of the substance. Yet that which is morall and naturall remayneth; it is still not only lawfull, but pious for the Jewes to set apart some times to prayse God for their deliverance out of Ægypt, and for those other blessings which that Church received from him, so that the typicall and properly legall use, together with the indispensable necessity of those particular times and ceremonies be cast away, it were no impiety in them, as matters of order, to make use of some or more of the same times which they formerly observed for this morall purpose. Yea we find St. Paul Acts 18:21, and 20.16 resolving and indeavouring to keepe one of those Jewish feasts at Jerusalem, long after the ascension of Christ, and the absolition of the ceremoniall part of the Jewish Law, and to take advantage of that solemnity to glorifie God amongst them. And if all this will not save you from a wonder, I intreat you to consider that the effect of the abolition of the Ceremoniall Law, was the taking away of the legall necessity and the typicall use of them, not the rendering of the matter of those Ceremonies unlawfull; and for your better satisfaction in this point, I refer you to a Treatise of mine lately set forth called, The sights of the Church and Common Wealth of England, pag. 312, 313, &c. where I hope you will find this matter abundantly cleared. And now the foundation of your seventh Quære being thus searched and found to be of so sandy a constitution, we need not trouble ourselves any more about the Quære it selfe: but to tell you in the words of a Reverend Divine, Quicquid nonnussi contra afferre solent pic & prudenter prospectus ost [?] ab Antiquis patribus, ut anniversarie in Ecclesia celebrarentur [?] ingeatis [?] illa beneficia incarnationis filli Dei, passe[?] is, resurrectionis, ascensionis, [?]issionis Spiritus Sancti, quorum [?][?][?][?][?] memoriam solemnitatibus constitutis consecranous, ne volumnine temporum ingratasurreperet nobis oblivie, ut loquitur Aug. de Civit. Dei. Lib. 10.c.4. Whatsoever some are wont to bring to the contrary, it was piously and prudently provided of the ancient Fathers, that there should be anniversary or yearly celebrations of those great benefits, of the incarnation of the Sonne of God, of his passion, resurrection, ascension, and of the sending of the Holy Ghost; the memorialls of all which, we consecrate by appointed solemnities, left, as St. Aug. speaketh, by the course of the times an unthankfull fortgetfullnes thereof should steale upon us. And the same learned Authour will shew you that we are invited heerunto by the obligation of gratitude that we owe unto God, as publique benefits are to be publiquely acknowledged, and to be celebrated with publique thanksgiving: which cannot commodiously be done, unlesse they that have the rule of the Church and Commonwealth, doe appoint set dayes for the people to come together to that purpose. Joel. 2.15.

That we are incouraged heereunto by the peoples benefit which they may reape heereby in being upon such occasions made acquainted with the chiefe mysteries of salvation, which whether they shall be instructed in, or no, is a matter of too great concernment, to be left to the discretion of every private Minister; and therefore the Church hath thought fit to call upon them for it by these Festivals. And I pray God the attempts of the abolution of these memorialls, be not the drifts of some secret plot of Sathan, to make way for the stealing of Christianity out of this Nation: if we consider the motions of some other engines of his, together with this in these times, I doubt wee may find but too much cause to suspect it, and cause enough for all good people to desire to prevent it, by being unwilling to part with any the least lawfull meanes, that may serve to keep up the memory and impressions of Christ, and his wonderfull mercies in our hearts.

He will shew you also, as I have done, how this practise is confirmed unto us by the examples of the godly people in the Scripture, who have appointed set and yearly dayes for such purposes, besides those that were commanded expresly and particularly by God himselfe. And I can adde that the same is yet further confirmed unto us, by the judgment and practice of holy men in the Christian Church, not only of the Ancients, but of many famous moderne Protestant Divines. As Melancthon, Hemingius, Scultetus, &c., all which being put into the same scale with the Authority of the Church of England, and the Law, which hath yet found no Authority equall unto it, to dissolve the Acts thereof in this kinde, will I doubt not weigh downe all the seeming reasons or divinity upon which you have grounded your Quæries.

To your eighty Quære.

Whether the true and genuine Interpretation of Christmas be Christ man? And whether to perswade people 'tis so, be not to abuse and delude them? And whether we may not as well interpret Candlemass Candleman, Michaelmas Michaelman, as Christmas Christman?

Answer, That this is a question so childish or so vaine importance, and so of no concernement at all to the businesse propounded: That I might be excused if I should say no more, but either to wish you more wisdome and sobriety in the things of God and his Church, or if you know any that is guilty of making so foolish a descant upon that name of Christmas as your Quære presents, to leave you to him for a Reply; neither the Church of England nor I are bound to justifie the follies of particular men: But least your insinuated quarrell at the name of Christmas, should meete with any such weake judgements, as to produce any scruple (premising this, that these are things that neither the Church of England, nor I conceive any discreet childe thereof will stand upon any further then they serve to make us understand one another, and I wish all quarrels about names were so at an end amongst us) I say yet further, that the interpretation of learned Bishop Andrewes might have beene better thought on by you, then that fond one you have mentioned, reducing Christmas to Christimissa, and taking missa for missio; so that it may present the importance of the Feast. Viz. The sending of Christ into the world, or if this be liable to some exception; yet it cannot be denied but the word Masse, however it hath been corrupted in latter times, is from missa, and I believe your may finde that the word missa hath been of some use in the Church, and derived from a good and laudable custome of dismissing the Catechumeni before the Communion in the Primitive times, and may import as much s the Office, or Communion of the faithfull, and then Crist-masse may found as much as the Office or Communion of the faithfull upon Christs day, or in the praise of Christ, or in memoriall of him; or if you are loath to admit of this in justification of the word missa, I intreat you yet to allow thus much: That however evill the word is in the use of the Church of Rome, yet since you know it hath no such evill importance in the sense of the Church of England (and it is not unlawfull to reforme the abuse of words as well as things) thee can be no harme in the use of that title for distinction, no more then it was for St. Luke in the 17 of the Acts v. 22 to comply so far with custome as to call the street in Athens by the name of Mars his street, although Mars were an Heathen Idol, or to call Dionysius by the title of the Areopagite v. 34. I advise you therefore to take the Counsell of St Paul hereafter, for your owne goode and the quiet of others, and the Church, that instead of being such a one as he condemneth, 1 Tim. 6.4.5. sick of a spiritual sympathy, and [series of Greek words], doating or madding about questions and strife of words, whereof commeth envy, strife, railings, evill surmisings, froward disputations of men of corrupt mindes, and destitute of the truth; you would become such as he adviseth, 2. Tim. 14.23. That you strive not about words, which is to no profit, but to the perverting of the hearers; and that you would put away foolish and unlearned questions, knowing that they engender strife.

To your ninth Quære.

Whether the Saints are bound to rejoyce in the Birth of Christ on that day men superstitiously call Christmas, more then a othertimes? And whether the Lords day be not (the) day appoynted for them to rejoyce on?

Ans. Leaving your imputation that you lay of superstition upon the name of Christmas to the correction of that which hath been already sayd unto the Quære next before. I answer, that though Christians are bound at all times to rejoyce in the birth of Christ, which is sufficient to condemne the boldnesse of those that forbid men upon any time or day to do it by that rule of the Apostle, Philipp. 4.4. Rejoice in the Lord alway, and againe I say rejoyce; yet to helpe our infirmities, and to stir up our backwardnesse, and to make for the greater cheerfulnesse and solemnity of this joy, the Church hath done well and piously to appoint some speciall times to call us together to rejoyce in the great mercies of God, and in that regard it is more especially required of all her Children to do it at such times then at other times, and the fault is the greater to omit it then, in as much as to the neglect of the universall duty is added the sinne of disobedience against the wholesome orders of the Church, and a division therein of our selves from the Body, and a denyall of that concurrence and assistance that wee ought to give in the communion and fellowship of Gods people in those things which are publickly performed for the celebration of the praise and worship of God, and for the advancement of divine comforts in the Congregations. And though it be true that the Lords day is a day wherein they ought to rejoyce, which yet as to the particular day, is but a holy circumstance, and a matter of order, though established by great Authority, notwithstanding it is not (the) day in such a sence, as your parenthesis would perhaps insinuate, as to exclude all other dayes from the businesse of solemne rejoycing in Gods mercies; for how then will the fifth of November, and the dayes of Thanksgiving, that have beene of late appoynted, be justified? and therefore your question makes nothing against our conclusion; for though that day be to be observed for a day of joy in God, it does not forbid others to be so employed.

To your tenth Quære.

Whether Christmas day ought in any respect to be esteemed above another of the Weeke dayes? And whether people may not without offence to God follow their lawfull vocations on that day?

Answer. In it selfe no day is necessarily to be esteemed better then another; for as the Apostle tells us, he that esteemeth all dayes alike doth it to the Lord. But in the use of it, as a matter of order, and as it is dedicated by a lawfull power in the Church, in a more especiall manner then the rest, in respect of obedience, order, and compliance with those sacred ends for which they are so designed, Christmas day, and other Festivalls of the Church ought to be esteemed above another day: For it is the duty of Christians to comply with one another and to obey Authority in those things that are profitable and conducible to holy and good purposes: And therefore it will follow, that without necessity, for people to depart from this Rule, and to doe it with contempt of Authority, and to the discouragement and hinderance of such holy ends and duties, by following their ordinary vocations which are lawfull at other times, is a breach of good order, a violation of unity, an hinderance to piety, and the holy Solemnity of such times, as well as to doe it upon a day of Fasting or Humiliation, instituted by humane Authority: and cannot be so done without an offence to God.

To your eleaventh Quære.

Whether you thinke the Parliament and Assembly have erred and played the fooles in condemning and rasing [?] out Holy dayes now warranted in the Word? And whether to observe them, be not highly [?]od sl[?]ke and flatly to contradict (in poynt of practice at least) their proceedings in order to a Reformation?

Answer. I doubt not to say that they have erred in divers respects: First, in making unnecessary changes in the Church, which ought not to be done, but upon urgent causes; but doth discover in them that doe it a love unto change, which the wise man condemneth, Prov. 24.21. and is ordinarily of evill consequence to the Church, as wee finde by too lamentable experience; for whilst the people like those that are sick of a Feaver have thought good mutationibus pro remedits uti, to take such charge for medicines, their remedies have proved their greatest diseases; and now wee see how sick they are grown of their Physicians, and how sick the Physicians are of their owne administrations: Secondly, they have erred in going about to abolish so harmlesse and usefull a meanes of the promoting of Gods glory, and of the edification of the people: Thirdly, inundertaking to dissolve so laudable customes, and so universally and anciently received, and established by full power of the State and Church, either without any Authority thereunto or by a power inferiour unto that, whereby they were constituted: Fourthly, in doing those things without any admission of those that are contrary minded to be heard, or any faire discussion or debate of those differences that are in mens judgements thereabout: and therefore their proceedings therein are, and may be justly disliked and contradicted both by declaration and practice, without lying open to any such charge as you mention of opposing proceedings in order to Reformation, properly so called; such undertakings with the rest that are like them, being rather in order to a deformation. But whether in this they have playd the fooles, or no, I leave that to you to determine.

To your twelfth Quære.

Whether (since most men and women in England doe blindely and superstitiously believe Christ was born that day) preaching on it, doth not nourish and strengthen them in that beliefe?

Answ. Although it be admitted to be a matter of some uncertainty whether our Saviour was borne upon that day, or not, yet (it being not materiall unto the lawfulnesse and wholsomnesse of the observation of the solemnity, as hath beene declared) if it bee an error in the people to apprehend so, yet it is an harmlesse one, and without the danger of superstition, which yet Preaching upon that day doeth neyther necessarily nourish nor strengthen in them. I shall not deny but there hath beene some difference in Antiquity concerning the very day upon which Christe was borne; but Hospinian, who was no friend unto the Church in these things, confesseth, That from the most ancient times, it was celebrated on the 24. of December; which hee prooveth out of Theophylus, a very ancient Bishop of Cesarea Palestina, who lived about the time of Commodus and Severus the Emperours. The Arguments that are brought against the reception of this day, for the very day of our Saviours Birth, from the imposition of the Taxe of the Romane Emperour, and from the shepherds watching of their sheepe by night, are not at all concludent, but of weake importance, to overthrow so ancient and received an opinion in the Church: Though that time might be lesse convenient for people to travell into their owne Countries, as was required in that imposition of Augustus, yet it is no strange thing in Magistrates, and those both prudent and pious, to passe through such small and private inconveniences for the obtaining supplies of publique necessities; it would be a very weake argument, if any should heereafter undertake to prove this unhappy Parliament began not in November, because that Moneth is usually none of the best seasons to travell from the several parts of this Kingdome to London in. And though sheepe are tender creatures, yet that season is not of the same bitternesse in all Climates, and if I mistake not, as tender as they are, they are even in this Northerne and cold Climate folded sometimes without dores in the winter: if the difference about this point be such that no certaine resolution can bee found, it is lawfull for the Church to make choice of such a day for the purpose of this solemnity, as appears most convenient. And what day more convenient, then that which as it is confessed to have beene most anciently received, so is commended too by the universality of the practise and consent at least of all the Westerne Churches therein? and if God be served and praysed by us in such holy and solemne maner as is due for so great a mercy, upon that day which the Church hath injoyned, it will be, no doubt, as acceptable to God, as if it were done upon some other day of your choyce, whether it be the very day of Christs birth or no: and I hope you doe thinke it fit, that some day or other may bee imployed in so good a businesse. The onely question then will remaine, whether the Church and Magistrate, or you bee fitter to choose, which is not worth the discussing.

To your thirteenth Quære.

Whether this Feast had not its rise and growth from Christians conformity to the mad Feast Saturnalia (kept in December to Saturne the Father of Gods) in which there was a Sheafe offered to Ceres Goddess of Corne; a hymne in her praise called [Greek title]? And whether those Christians by name, to cloake it, did not afterwards call it Yule, and Christmas (as though it were for Christs honour?) And whether it be not yet by some (more ancient then truely or knowingly religious called Yule, and the mad playes (wherewith 'tis celebrated like those Saturnalia) Yule games? And whether from the offering of that Sheafe to Ceres; from that song in her praise; from those gifts the Heathens gave their friends in the Calends of January, omnis [?] gratia; did not arise or spring our blazes; Christmas Kariles, and New yeares gifts?

Answ. That the originall and growth of so pious and holy a practice in the Christian Church, should be allowed no other root but a supposed confirmity of Christians to the madde feasts of Saturnalia, when there are so many better and clearer fountaines to derive this from, in the order that it hath unto Scripture end and duties, to Gospel and Christian performances, and in the warrant that it hath from Scripture examples in like matters, is an argument of some want of charity in those that goe about to infect men with such perswasions. Charity engageth us to judge the best even of the actions of private men, much more of the publike constitutions and observations of the Church; whatever abuses have beene brought in by wicked and loose men to corrupt and deprave these wholesome ordinances, (which we approve not nor will undertake to justifie) There is no confirmity nor compliance at all, betweene the holy aymes and intentions of the Church of God, in the appointment of this or other festivalls, and thte franticke, loose, and impious manage of the Saturnalia among the Heathens. These are appointed by the Church to bee dayes of piety and sobriety, of prayse unto God for his great mercies, of spiritual joy in his divine comforts and holy delights in our Christian societies, of hospitality and mutuall offices of Christian love one to another, which are the true and proper employments of holy festivalls, commended and warranted unto us by the word of God. If any practises have crpt in (as there have too many) to the depravation of these times, and disappointment of those ends for which they were instituted, by riot and loosenes, or such rude cariages and demeanours which may be too truly sorted with the Heathenish Saturnalia, they have been anciently reproved, as Hospinian will informe you by that which hee hath cited out of that famous Oration of Gregory Nazianzen upon the Nativity of Christ: And he will tell you a Sory too if you will beleeve it of one Otherus and some others to the number of 15. who being reproved by Rupertus A Priest for prophaning that night of our Lords Nativity, by light and lascivious dancing and singing, and required from him, ut ab hujnsmods la vitate in nocte tam sancta desisterent: That they would desist from such lenity in so holy a night, when they would not yeeld unto this wholesome advice, But persisted in the vaine exercises they were about, upon the prayer of Rupertus that they might continue dancing so all the yeare long, They did so continue night and day for the space of a whole yeare: and he cites Trithemius in chron. Hirsang. for the Author of this Story; which if it be true doth not at all the oppose, but confirme these constitutions of the Church, as the judgements of God sent upon those that are the prophaners of the Lords day, are brought to justisie the obsevation thereof; it doth indeede disallow the abuses thereof, which as they were anciently condemned, so wee condemne them still, being contrary as to the righteous commands of God, so to the wholesome institutions of the Church: I earnestly exhort all Christians carefully to avoyd all such courses and miscarriages, and to sanctifie this and other such like Festivalls unto God in holy and Christian duties as they ought, and the Church enjoynes, left they answer the contrary d[??]rely unto God, as well for the enormity of their virious carriages, as for the prophanation and scandall that they thereby bring upon these profitable Orders of the Church, and their sacrilegious robbing of God of such times which are consecrated to his Divine Worship, That they may employ them in the service of the Devill: But in the meane time I cannot but wonder at the strange dispensations of these times, wherein for ought appears, there is more strictness used against the preaching of the word of God, and holy exercises upon these dayes, then against any of the foresayd abuses and miscariages. Wee have heard of the persecution and imprisonment of Ministers for attempting to preach the Word of God, upon the festivall of Christs Nativity, and of strict and forcible prohibition thereof; but whether there hath beene halfe so much strictnesse against riot, or lightnesse, or vanity, at such times, let it be considered; and surely such dealing is no good character of a Reformation. They that do so, winnow not with Gods sieve, but the Divels, shaking out the wheat, and retayning the chaffe; they are no good Physicians, that purge out the good and wholesome humours, and leave those that are corrupt and distempered behind, nor is this the way to procure health unto the body. In the name of God if they meane to reforme, as they talke, let them distinguish betweene good and evill, betweene healthful and profitable institutions, and pernacious and abusive depravations, and let these be removed, and those established if it doth appeare that the time of this Festivall doth comply with the time of the Heathens Saturnalia, This leave no charge of impiety upon it; for since things are best cured by their contraries, it was both wisedome and piety in the ancient Christians, (whose work it was to convert the Heathens from such as well as other superstitions and miscarriages) To vindicate such times from that service of the Devill, by appoynting them to the more solemne and especiall service of God and to recall people from that practise of wickednesse by calling them unto the practise of true holinesse thereupon. As for that you adde about your Yule games, it is not materiall, after that which hath beene sayd, and therefore for brevity sake I passe it over. The Blazes are foolish and vaine, and not countenanced by the Church. Christmasse Kariles if they be such as are fit for the time, and of holy and sober composures, and used with Christian sobriety and piety, they are not unlawfull, and may be profitable, if they be sung with grace in the heart. New yeares gifts, if performed without superstition (and you must have ground ere you may charge them without it) may be harmless provocations to Christian love, and mutuall testimonies thereof to good purpose, and never the worse, because the Heathens hve them at the like times. The Heathens use to eate at noone, and so doe wee, if it be harmlesse to joyne with them in houres designed for acts of nature; why not in dayes designed by us for acts of love and mutual affection; if those dayes and their practice thereupon be tainted with superstition, it will not follow that ours must needs be so, or is it now lawful for us to employ those dayes well, because they doe ill? But this is no Religious but a Civill matter, and therefore not requisite to stand much upon it; no great matter whether that custome be held up or no, and yet there is no need in such times as these to discourage and forbid acts of love and mutuall kindnesse. This Age is not sick [?] of any superstuities in this kinde in the general, and therefore no great needs of physick for such diseases: Trouble not your self therefore any more about this matter; if you dislike New-yeares gifts, I would advise your Parishioners not to trouble your conscience with them, and all will be well.

To your fourteeth Quære.

Whether confirmity to, and retention of Heathenish Customes be commendable in Christians, sutable or agreeable with Gospel Principles, though under pretext of Christes Honour and Worshippe?

Answer. You seeme to me to be ignorant, and have taken up opinions at too easie a rate; give me leave therefore to informe you a little: All Customes are not Heathenish that are observed among Heathens; it is a custome with Heathens to kneele at prayer, yet this is no Heathenish custome; it is a custome with Heathens to institute publique Fasts, and dayes of Humiliation in times of danger and calamity, will you say therefore that Christians are Heathenish, or comply with Heathenish customes in doing the like? Or if wee may joyne with them in appoynting dayes of fasting, why not as well in appoynting dayes of feasting, as long as wee joyne not with them in superstition about either? Wee must not deny Christ because the Devills confessed him. It is no good Christianity in the people of this Age to hate their brethren, because the Publicans are friendly unto theirs, Math. 5.47. Wee are not sure bound to prophane all times that the Heathens have superstitiously consecrated, if wee are, I doubt you will scarce have halfe an houre in the day or night left you for your devotions: Wee may joyne with Heathens or any in those things, that are good and wholesom. Heathenish customes cannot be good, but many customs of Heathens may: They have learnt, it is probable many practices of Religion from the people of God, and have corrupted the Coppies that they have taken from the Originalls, it is not necessary therefore for Gods people to cast away the Originalls which are pure and good. Heathenish customes are such as stand opposite to the doctrine of Christ and the Gospel: The Religious observation of these Fewstivalls makes for both; to appoyne and observe a day holyly and religiously for the solemne praise of God for Christ, and Gospel mercies, cannot be sayd to be against Christ or the Gospel; since the former is honoured, and the latter preached and published by this meanes: This therefore is no Heathenish custome; take you heed of complying with an Heathenish designe of abolishing the memory of Christ and Christianity from amongst us, it is a danger worthy of a double caution, it is not a pretext of Christs honour. But the truth thereof that justifies these dayes, and is the proper and holy business of them; wee desire not to march under such colours, but leave them rather to those that under pretext of Religion are busie to overthrow all Religion amongst us: I neede not tell you who they are, but wish you take heede of them.

To your fifteenth Quære.

Whether you re not bound to prove your practice for the conviction and satisfaction of your Brethren, whose duty it is to walke with you in things agreeable to the minde of Christ? And in case you cannot; Whether you ought not to acknowledge your errour, lay downe your practice (as others have done theirs) no longer befooling and misleading the people committed to your charge?

Answer, I have sayd thus much for your conviction and satisfaction, and with it may worke to well with you, that as it is your duty, so it may be your practice to walke with us in things agreeable to the minde of Christ; and therefore I hope wee are sufficiently discharged from any necessity of confessing any errour in these thinges, and that it doth by this time appeare that there is much more neede of reforming yours, and of laying downe your practice as others have done theirs, no longer befooling nor misleading the people committed unto your Charge; that you may from hence forth teach them the wayes of peace and righteousnes.

To your sixteenth Quære.

Whether in case you returne no Answer to these Quaries, I have not ground sufficient to conclude you utterly unable to give any rationall account of your practice, now put upon it?

Answer, Sir, you have an Answer to your Quæries, and therefore have no ground left you sufficient to conclude us unable to give any rationall account of our practice, which I wish you may receive with a Christian minde, that you and others may reape the fruit with a Christian minde, that you and others may reape the fruit thereof: Let your Study be Unity, for that is the way to felicity.

The God of peace and holynesse direct you and us all into the wayes of peace and holynesse, that wee may no longer foster divisions and strife amongst us, to the joy of our adversaries, and the reproach of the Gospel; but that following the truth in love, wee may in all things grow up into him, which is the head, even Christ.

--------

Nor for all the paines I have taken to answer your Quæries, I shall desire you to answer but one of mine, viz.

Whether you think doth savour of most piety and good will unto Christ and his honour, to forbid the preaching of Gods word, and the celebration of the praise of God for his great mercies upon the 25 of December, or upon any other day, or to enjoyne it? Or whether it becomes Christians to prohibit the worke of God at any time?

Tuesday, December 20, 2011

A Medieval Christmas Carol

From: Jokinen, Anniina, ed. "What Tidings Bringest Thou." Luminarium.

26 Nov 2009.

What Tidings Bringest Thou?

:: What tydynges bringest thou, messenger,

Of Christes birth this Yoles day? ::

A babe ys born of hye nature,

Is prins of pes & ever shal be.

Of hevene & erthe he hath the cure,

His lordshyp is eternite.

Such wonder tydyngys ye mow here,

That man is made now Godys pere,

Whom synne hadde made but fendes praye.

:: What tydynges bringest, &c. ::

A semely syght hit is to se,

The berde that hath this babe y-borne

Conceyved a lord of hye degre,

A maiden as heo was byforne.

Such wonder tydyngys ye mow here,

That maide & moder is one y-fere,

And alwey lady of hye aray.

:: What tydynges bringest, &c. ::

This maide began to gretyn here childe,

Saide: "Haile sone, haile fader dere!"

He said: "Haile moder, haile maide mylde."

This gretynge was in queynt maner.

Such wonder tydyngys ye mow here,

Here gretynge was in suche maner

Hit turned manys peyne to play.

:: What tydynges bringest, &c. ::

A wonder thynge is now befalle;

That lorde that formed sterres & sunne,

Heven & earth & angelys alle,

Nowe in mankynde is byginne.

Such wonder tydyngys ye mow here,

A faunt that is not of o yere,

Ever hath y be & shal be ay.

:: What tydynges bringest, &c. ::

Notes:

Yoles day - Yule Day; Christmas Day.

hye - high

prins of pes - Prince of Peace.

Of heven... cure - he has power over heaven and earth.

wonder tydyngys - wondrous tidings.

mow here - may hear.

Godys pere - God's peer.

fendes praye - fiend's (Devil's) prey.

semely syght hit is to se - pleasing sight it is to see.

berde - maiden.

hath this babe y-born - has given birth to this child.